From the trenches: Resilient workflow processing

Subscribe

Pub

Share

While with Sigma Systems, I had the opportunity to, among others, design, build and/or contribute to 4 different generations of -what we called- workflow or work-order processing systems: dedicated and optimized for enterprise integration, generally targeted for telecommunication providers' integration patterns. Each generation was built upon the knowledge and experience emerging from the previous generation, evolving not only in terms of environment from C++ to Java to J2EE and from proprietary messaging to JMS with XA and then back to proprietary messaging, but also from microservices to J2EE monolith and back to microservices.

Don't be confused about the notion of workflow - I'm not talking about my grandma's document workflows, but about high-performance, high-throughput, low-latency, highly-available carrier grade processors, deployed in 30+ production environments, where "failure is not really an option", serving well over a hundred million subscribers. By "failure" I mean failure of the system as a whole, not individual component failures: these are expected.

Resilient: The system stays responsive in the face of failure. [...] Resilience is achieved by replication, containment, isolation and delegation. https://www.lightbend.com/blog/reactive-manifesto-20

It is this last aspect that I find one of the most interesting, the fact that we design them with resilience as a primary goal and a big part of resilience turns out to be, believe it or not: simplified dev/ops, a result of fault-tolerance and self-healing (recovery).

It is surprising how uncommon these traits are, although they could apply to any kind of large-scale "entity" processing system... let's take a look at what they meant in our context.

Architecture

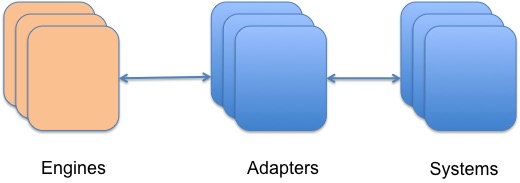

The architecture we kept coming back to was one typical in enterprise integration environments, where more processing engines were connected to a layer of "integration adapters", which executed the activities asynchronously, while maintaining connection pools to the downstream systems involved and taking care of retries, recoveries etc. If you call these adapters asynchronous fault-tolerant resource managers, you'd be close enough - they offered another layer of insulation or bulk-heading.

Just like in actor systems, in a resilient distributed system, message-passing decouples the components and, together with location transparency, forms the basis for resilience.

Message passing

The basic underlying architectural aspect that allows this level of resilience is the fact that the entire system is designed as a set of asynchronous components, decoupled via message-passing. It matters not if the actual protocol for message exchange is an http connection, as long as the logical sending and receiving threads do not need to synchronize in order to exchange the messages - that's the important bit. After all, many messaging systems use session-based TCP for the actual transmission of data.

Thinking through this simple idea will reveal several implications for the way messages are tied to resulting state transitions - there are several patterns that can be used, very common being Guaranteed Delivery, with "at-least-once" semantics.

Note the decoupling between the sender and receiver.

We used a few messaging and routing systems and hacked some, including a few JMS implementations, Akka, Camel and more, but also built a few in-house, with an ever increasing set of features, including "fault-tolerance" and "unit of order", cooperating with the application logic to ensure "only once" execution, although different parts achieved "at least once" semantics.

Fault-tolerance

Fault tolerance is a basic trait of a resilient and highly available system, where clients are insulated from faults within the system and the system itself continues operating, albeit with a degraded performance, in the event of failure of one or more components.

To put this in terms of the entities being processed here: even if one or more of the workflows processing engines were to fail, the system will still:

- continue to accept new workflow requests

- continue to process and complete all workflows in progress

After many revisions, the best way to implement this turns out to be at the messaging system level, via location transparency, where the messaging subsystem is aware of the status of the cluster and individual services and can re-route messages to other nodes, in order to deal with failures. The messages are either requests for new workflows or continuations for the flows in progress (work requests, replies or notifications).

Also - related to location transparency in this architecture, since all messages refer to workflow instances - the simplest way to ensure some level of performance is to assign a workflow to an owner node and route all replies back to it by default, except when this node fails, in which case it can be routed to another engine, which will attempt to take ownership - designing distributed ownership algorithms is hair-rising, but fun! If you can get decent performance without this kind of optimizations, you're in a better position.

Self-healing

Self-healing is a different trait, important for resilience: either the failed nodes can recover (being rebooted/restarted by a supervisor for instance) or new nodes can elastically be added, to take their place.

Depending on the underlying technology, recovering existing failed nodes may be a must, in cases where it is not easy to migrate work in progress, off of the failed nodes (as is the case in some JMS server implementations). In this case, the same node needs to be restarted, to pick up its work and finish it, or some other node needs to take its place and impersonate it - in this case we say the system is designed with a strong node-identity - this is frowned upon these days, as cluster managers like Kubernetes don't handle it well.

Let-it-fail

Let-it-fail means literally "let... it... fail", i.e. allow the entire process to fail and bounce, when failures occur (or at least when specific or unknown failures occur). The idea is that the specific process may be "dirty" and may become unstable, so it's easier to bounce it.

This implies having a supervision strategy in place (i.e. configuring the Docker daemon), because the process can't restart itself - it is better to have an external supervisor, which detects failures and restarts the process. Custom supervisors like NodeManager (in Weblogic), Monit or the Docker daemon fulfill the bill at the process level. It is generally a good idea to let the entire process bounce as opposed to restarting just one thread or one actor - since memory and resources are shared within one JVM.

It is important to have a ping service or health check endpoint, one that will respond not only if the process is up, but also if the process is healthy (hint: how do you detect threads that are stuck?).

While this is a critical ingredient for resilience, it requires that the code of the respective components is written in such a way that the components can be killed at any point and can recover upon restart, including commit or rollback of any transactions or work in progress.

While XA (distributed transactions) may sound like a great match for this, I have never seen an implementation where it worked as advertised in the face of complex failures scenarios). There are better ways to deal with coordinating resources, including the Saga pattern and other EIP patterns, which have the added advantage of reducing the time any set of resources are acquired together.

We'll look later at the fact that we're using the workflows themselves to coordinate resources, in essence, so they are themselves an alternative to distributed transactions. If you're used to XA, this is definitely something you should look at.

Bulk-heading

Bulk-heading refers the principle that requires breaking down the system into components and then separating and insulating the different components, so that when one component fails, the others can continue.

It's not as easy as it may sound - you will sometimes find that some of the infrastructure used breaks the principle of bulk-heading - so always pay attention to hidden dependencies - these can be as simple as a distributed database lock.

I remember an instance where a large production cluster kept failing and could not recover even after rebooting all the nodes, even though all the nodes were separated: each had its own JMS server and poison message queues and circuit-breakers and whatnot... long story short, it turns out that the JMS servers within each Weblogic node relied on a singleton "admin server", in case of repeated failures. This server was not meant to be ever involved in the processing path, so it was never sized to have more than 5 threads. So when the individual nodes were subjected to a flurry of poisonous messages, each JMS server tried to notify the admin node synchronously, which itself was trying to manage some more resources in response, causing the entire cluster to deadlock.

Yeah - who would have thought that the one component we relied on for asynchronous communication would in fact turn out to reduce everything to one single synchronous call and even more than that, subject to a simple deadlock situation.

Of course, when it happened, this also locked us out of the "admin console" which ran on the same "admin node", now starved of "admin threads".

One simple bulk-heading technique I already mentioned was taking the "integration adapters" away from the main processing engine: bugs are more likely in custom integration code, so by separating these from the main engine at the process level, it insulates the system better against memory eaters, connection poisons and the like.

For maximum isolation, each adapter could be its own process.

Back-pressure

The same sort of thing occurs when you do back-pressure the wrong way.

Back-pressure refers to the way a system deals with overloading - when one component cannot keep up and needs to slow down accepting work requests.

If you size all the thread pools and all the connection pools properly, do all your dependency and boundary analysis and then just let the system naturally do back-pressure through socket listener limits for instance, you may run either out of memory or out of sockets: while easy, it is risky because running out of sockets may also lock out administrators (or the automated supervisors) exactly when they need access the most.

It has been my experience that slow-downs always occur. Somebody runs a slow query in a database and that suddenly impacts your updates. Or, the system finds itself in more sneaky and hard to debug situations, say when firewalls are configured poorly and slow down certain traffic (like RMI) without any warning.

Whether back-pressure is implemented properly, in a system that can afford dumping some responsibility to the clients... or not, in a system that "must" deliver even though on a degraded basis, is a secondary concern, but an important one. Even a simple "store and forward" decoupling strategy (or a smarter managed queue) will contribute to increasing the resilience significantly, in the absence of proper back-pressure.

In our case, putting customers on hold when some component was slow, was not really an option, so we always took care to accept new orders quickly, back them up and promise they'd be completed eventually.

Testing

Testing is as big a part of resilience as anything. Without serious and long running heavy stress testing, you cannot claim the result to be resilient, in my mind not even with the best "clean room engineering" approach.

We use long running testing under load, on fairly sized clusters, where errors are introduced randomly and nodes shutdown and restarted frequently, while errors and success are closely monitored.

One lesson learned here is to not limit the testing to the known transaction mix, but try the extremes as well. You may well find out that in a lean period of high volume of low latency transactions, some components overheat well beyond what you'd otherwise expect. I seriously treat the entire system like an engine at this point and try hard to cause a run-off.

Probing all production environments for resilience issues is important as well - otherwise small problems that are otherwise like canaries are to miners, may go unnoticed.

See more in: Cool Scala Subscribe You need to log in to post a comment!